Published on August 01, 2023

Author: Andrew Della Vecchia

Preface

In this article, I will be using some Python code to experiment with random numbers. Along with that, you will notice I will also add in a bit of R too. I do find the Python vs R battle a bit unnecessary and limiting. Do not forgot there are other packages, such as SAS, that are still popular.

The choice of languages might be a touchy topic for some. Everyone seems to have favorite trinkets and even the calmest discussions can quickly devolve over this topic.

Programming languages do come in many different flavors, such as functional, imperative, and object-oriented. When it comes to picking one for a project, it should be a matter of deciding according to what needs to be done. This is simply not the case in the real world.

Consider that there are some languages that are touted as the only one you will ever need to learn. These can become popular then eventually just linger around. Some will even die out or get killed (J# anyone?1). It would be devasting for a project’s long-term survival to have been built using one of these languages.

In the world of technology, there are often battles so strong on the superiority of one language over another that war poetry has been written. I wear many scars for having jumped into these battles over the years. Those scars are very important to me.

It is essential to level the scholarly factor of a programming language with real-world experiences. An informed decision on architecture will lead to more project success than one based off trying to shoe-horn technology that meets the latest trends.

Remember, only fools rush in.

Series Introduction

I am trying something different with this article. Instead of stuffing-in much information into a single post, I will break up the topic into a series of articles. The topic I am going to explore is with numeric randomness. There are many articles, books, and various social media posts that already discuss the components of random numbers. My goal and hope with this series is to try to get a small bit of an analytics slant to this topic. I will also provide a series of simple experiments. I am hoping that this exploration is one that you will enjoy.

Define Random Numbers

There are already many web pages with definitions for what is a random number. I think they try too hard. Some definitions have many layers while others dive deep into formulas. It can be too much to grasp in one breath. I think understanding random numbers requires more of journey and that requires a single step forward. I will start with that first step to say that a random number is simply one that cannot be guessed.

What is so great about a random number?

Random numbers can be easily taken for granted. The term gets bounced around but think a bit about it for a second. What can be said for a bunch of numbers that are just sequential?

1…2…3…4…5…6…7

What number do you think is next? What if instead of the obvious 8, it was 42?

1…2…3…4…5…6…7…42

You would be thrown off thinking you do not quite understand what is happening. Instead of a predictable series of numbers, you are unsure of what the next value can be. The mind begins many different machinations at this point. You might take a complete guess and get it right or you might think of a pattern or algorithm only to get it completely wrong. Whatever the result, you are now in the realm of cracking a random number generator (RNG).

There are many applications for RNGs. The one often thought of is with cryptography and its many implementations2. A perfect series of random numbers would be very useful in this field. If you cannot crack the RNG used for cryptography, that is certainly one very strong method for keeping you out of information the owner would not want you to know.

There are also uses for randomization in democracy. In the United States of America, we have a random polling system for picking citizens for jury duty3. It might not be the most enjoyable or convenient task for someone to do yet it is an example of the use of randomness. From a list of prospective citizens, everyone has a chance of being picked to make sure there is good representation from the population.

There are other uses such as with games. A game AI using a predictable RNG for action diversity certainly would make for an easy or frustrating experience4. Some joking aside, random numbers are useful in many things including political and military planning. Given this blog tries to focus on data, what about the uses of RNGs with analytics?

Statistical Sampling

Processing large sets of data can be interesting. In many cases, you cannot just gather the entire population data set. You might get a good size set of the population, or you might get enough to run basic metrics. How do you then ensure that there is good representation without selection bias? A RNG would be useful.

As an example, take the Heart Disease Dataset. Here it would be extremely difficult to get the entire population of the world’s heart measures. Instead, you get what has been measured5. These data might come from someone with heart disease or they might be from healthy persons. Taken a step further, you might get all males or you might get all females but you probably get some from both genders. Random sampling is one technique to create a set of records to measure without introducing bias.

Take the following samples. It is set to 10 records each.

| age | sex | cp | trestbps | chol | fbs | restecg | thalach | exang | oldpeak | slope | ca | thal | num |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 44 | 1 | 3 | 130 | 233 | 0 | 0 | 179 | 1 | 0.4 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| 61 | 1 | 4 | 120 | 260 | 0 | 0 | 140 | 1 | 3.6 | 2 | 1 | 7 | 2 |

| 57 | 1 | 4 | 130 | 131 | 0 | 0 | 115 | 1 | 1.2 | 2 | 1 | 7 | 3 |

| 63 | 1 | 4 | 130 | 254 | 0 | 2 | 147 | 0 | 1.4 | 2 | 1 | 7 | 2 |

| 64 | 0 | 3 | 140 | 313 | 0 | 0 | 133 | 0 | 0.2 | 1 | 0 | 7 | 0 |

| 63 | 1 | 4 | 140 | 187 | 0 | 2 | 144 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 7 | 2 |

| 51 | 1 | 1 | 125 | 213 | 0 | 2 | 125 | 1 | 1.4 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 0 |

| 51 | 0 | 3 | 120 | 295 | 0 | 2 | 157 | 0 | 0.6 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| 44 | 0 | 3 | 118 | 242 | 0 | 0 | 149 | 0 | 0.3 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 0 |

| 51 | 0 | 3 | 140 | 308 | 0 | 2 | 142 | 0 | 1.5 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 0 |

| age | sex | cp | trestbps | chol | fbs | restecg | thalach | exang | oldpeak | slope | ca | thal | num |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 66 | 1 | 4 | 112 | 212 | 0 | 2 | 132 | 1 | 0.1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 2 |

| 62 | 0 | 3 | 130 | 263 | 0 | 0 | 97 | 0 | 1.2 | 2 | 1 | 7 | 2 |

| 71 | 0 | 4 | 112 | 149 | 0 | 0 | 125 | 0 | 1.6 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| 49 | 0 | 4 | 130 | 269 | 0 | 0 | 163 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| 57 | 1 | 4 | 165 | 289 | 1 | 2 | 124 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 7 | 4 |

| 59 | 0 | 4 | 174 | 249 | 0 | 0 | 143 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 1 |

| 64 | 1 | 4 | 145 | 212 | 0 | 2 | 132 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 6 | 4 |

| 60 | 1 | 4 | 130 | 206 | 0 | 2 | 132 | 1 | 2.4 | 2 | 2 | 7 | 4 |

| 37 | 0 | 3 | 120 | 215 | 0 | 0 | 170 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| 54 | 1 | 4 | 120 | 188 | 0 | 0 | 113 | 0 | 1.4 | 2 | 1 | 7 | 2 |

The 2 sampled groups are distinct enough for analysis and that uniqueness is thanks to randomness. *Please note this huge caveat that this is a very basic example. Sampling theory is quite large. I highly recommend you spend time with various learning materials to really appreciate what is done to avoid bias.

Random Networks

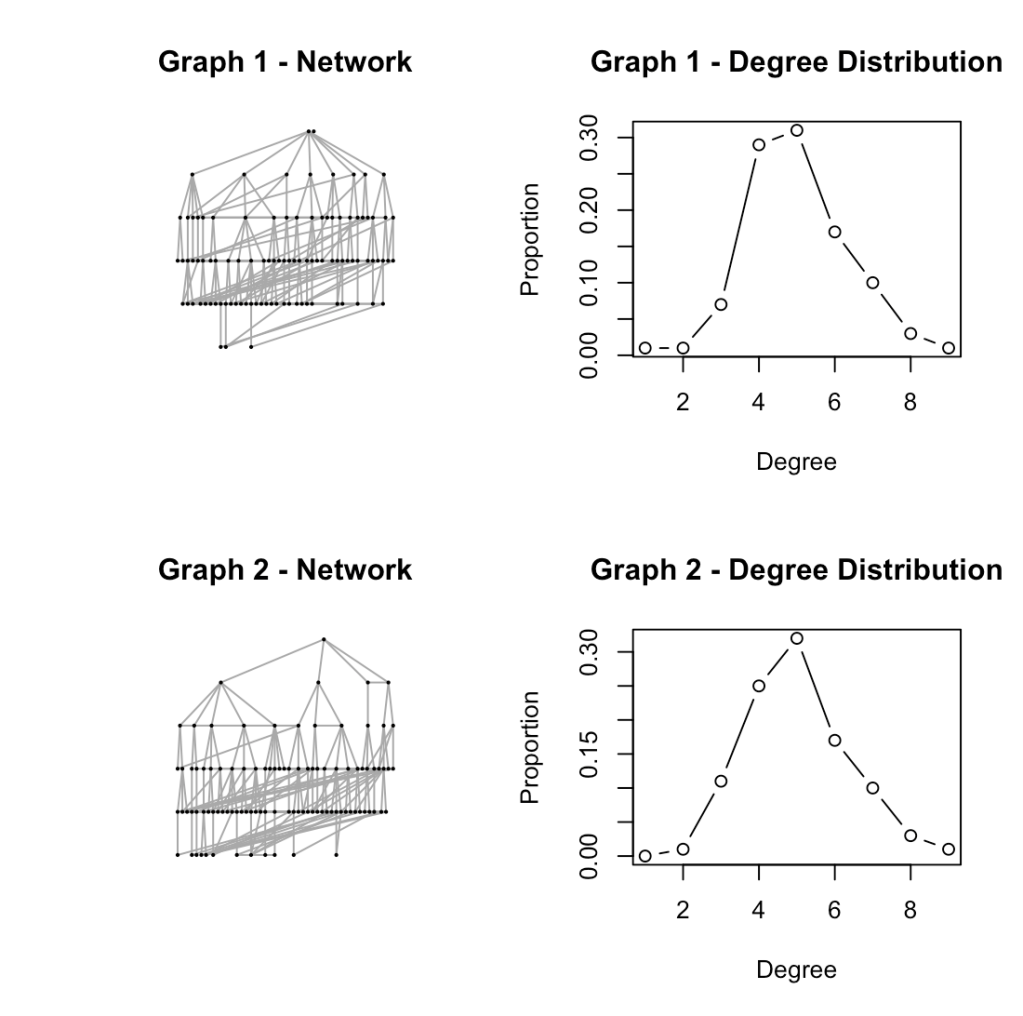

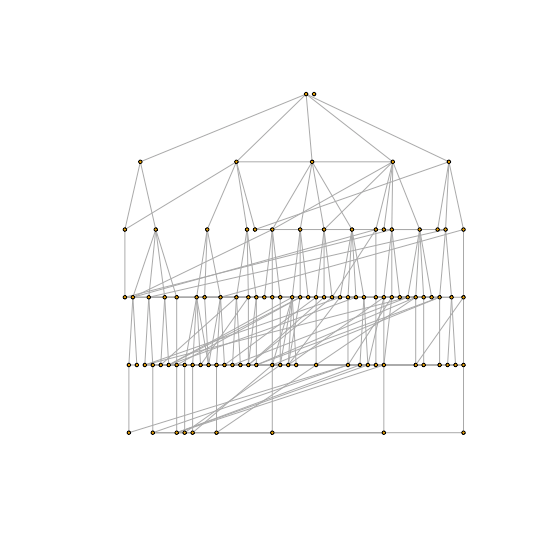

Another way RNGs help with analytics is when studying social networks. Graph theory is a great study expanded every day by mathematicians, analysts, and anyone else interested (never forget that anyone with a willing and curious mind can learn, grow, and experiment). All different networks are created with the help of RNGs to form different structures for modeling theories. The process of developing random networks is done many times over. Analysis is done to see what patterns might or might not form6.

One type of network we can look at is the Small-World Network7. You might remember this from the “six degrees of separation” trend from years ago8. If not, I recommend that you read up on the Small-World Experiment from Stanley Milgram9. What this network shows is how connections are made via proximity to the neighbors.

I can show this type of network with just a little bit of R code. First, 2 separate graph objects are created using the wonderfully useful igraph library10. Then, I will plot out the networks in a tree layout along with a closer look at the degree distribution.

You can see that there is randomness between the 2 graphs from the tree alone. What is interesting is the degree distribution. There is some similarity in the general shape of the 2 plots. Maybe in a future article I can explore what would happen if I generated many random graphs then averaged them all together. Would they form the same pattern? Ponder that and start doing some coding while thinking “what do graph theorists think about regularly?”

Start to see it?

These examples are important ones but keep an open mind. There are many other things to imagine. Can you see randomness in predictions? How about preparing for various disaster scenarios? Can everything be predicted?

If everything happened according to a known plan all the time, we could contain day-to-day life in a well-kept, evenly creased, little box. Nothing could ever go wrong without a prepared response ready to meet it.

Since absolute prediction of every event is far out of the grasp of the current state of mankind, we must respect and use randomness as part of day-to-day living. Having that thought churning through the back of my head, I will need to explore deeper.

Pseudo RNG?

There are some interesting aspects to RNGs. The first discovery is well grounded in reality. Even though that term “random” is used, a RNG really is not truly random. In fact, the well-known term in mathematics and computer science is PRNG which stands for Pseudorandom Number Generator. What then is pseudo about it?

They are Pseudo-RNGs because they are built using deterministic machines. That fancy term means that given a defined algorithm with the same input(s), the output(s) will always be the same. If that were not the case, how could anyone trust the machine for a consistently correct answer? If I create a simple program that follows:

start

let a = 1

let b = 1

let c1 = a + b

let c2 = a + b

If c1 is not equal to c2 then

Print “Check that the machine is functional”

end

It is always expected that c1 will be equal to c2 as that is reality of basic addition with 2 integers. If not, there would be a question on whether the machine and its parts are reliable (ex: Intel FDIV Bug11).

If the outputs are always consistently based on the inputs, how can anything random be generated? That is a very good question, and that demands exploration.

Using a deterministic algorithm that feeds back itself is one clever way to create these PRNGs. Part of the algorithm uses a special, very important input, called a “seed” value, then generates a seemingly unexpected number as an output to represent a random value. That output is typically used as the next seed value put back into the algorithm for the next random value. This process continues on and on with each call to the PRNG.

When you look at these PRNGs12, pay attention to how well the seeds are generated. Some seeds are merely sequential while others get extremely complex. A quick example is to use the date and time values from an available clock. Other approaches get even more resourceful with seed generation.

A very interesting method of creating a seed is to look to non-algorithmic solutions. One example can be seen in measuring the static coming from unshielded electrical components such as a resistor. If an electric signal is passed along a circuit containing a noisy resistor, a measured value from the component’s erratic behavior could be used to make a seed. In fact, the Trusted Platform Module13 in many modern machines uses an advanced version of this approach.

I hope you are now considering the power of these seeds. What could be done if you had a method of calling the PRNG and knew exactly how to generate the seed to repeat the results? If there were a way to do this for a casino game, that would put the house in a different odds ratio for winning against you. This makes seed generation a very critical part of the RNG development.

There are other aspects. Sometimes, if the RNG is built using a not-so-very-good algorithm, you will not only get predictable values, but you will also get repeating values. RNG quality metrics must be considered.

Quality

You might now start to wonder about the different impacts of RNG quality. Take an example with sampling of the population for juror selection. What if the randomness is poor and the same people are picked repeatedly? That would bias the judicial system which is a troubling thought.

How about with cryptography? What if the random numbers used for generating various encryption keys are easily guessed or repeated? It could be exploited by nefarious thinking individuals to cause harm to a person or many persons.

Fortunately, there are different methods for testing RNGs. A more in-depth exploration of those analysis techniques is best for a separate article. For now, let us go through and run some basic experiments to demonstrate some holes in a PRNG.

Experiments

Experiment 1 – Guessing Game with 2 PRNGs

This experiment will be direct. I will test whether the coded process will generate the exact same number using 2 instances of a PRNG with 2 different seeds. For this and all experiments, when the 2 numbers are equal, a “hit” will be registered. If they are not equal, then it will be considered a “miss.”

I will use Python here as it is used extensively these days for many different solutions. A developer could use different libraries, but the easiest to reach for is the Random Module14. Under the hood, this uses the Mersenne Twister Algorithm15. I will not offer an opinion but will state this is still a PRNG so it is crackable with enough determination behind it.

I will setup the 2 PRNGs using different seeds. First, I am going to initialize these seeds in a basic fashion to 100 and 200. Then, I will try a bit more spread out and odd shaped and initialize the seeds to 36912 and 707. As each iteration goes forward with each trial, I will let the state of the system continue. Resetting the seeds at that point would cause the expected result of repeating previously found hits.

There needs to be other parameters as well to really make it interesting. I will set a range for each trial. At first, it will be a simple 0 to 100. For each subsequent trial, I will expand the range by factor of 10. Then, I will let the process run till it gets a first hit or a limiter on the number of tries is reached (10,000,000,000 tries sounds basic enough). Will there be a case where the limit happens before that trial limiter is reached?

Results from first run with seeds 100 and 200:

+-------------+-------------+--------------+-------------+------------------+

| trial_num | low_fence | high_fence | first_hit | execution_time |

+=============+=============+==============+=============+==================+

| 0 | 0 | 100 | 60 | 96.666 |

+-------------+-------------+--------------+-------------+------------------+

| 1 | 0 | 1000 | 758 | 1173.54 |

+-------------+-------------+--------------+-------------+------------------+

| 2 | 0 | 10000 | 652 | 1049.75 |

+-------------+-------------+--------------+-------------+------------------+

| 3 | 0 | 100000 | 71565 | 110974 |

+-------------+-------------+--------------+-------------+------------------+

| 4 | 0 | 1000000 | 200237 | 303510 |

+-------------+-------------+--------------+-------------+------------------+

| 5 | 0 | 10000000 | 4930988 | 7.97454e+06 |

+-------------+-------------+--------------+-------------+------------------+

| 6 | 0 | 100000000 | 165839665 | 2.63223e+08 |

+-------------+-------------+--------------+-------------+------------------+

| 7 | 0 | 1000000000 | 923259852 | 1.42905e+09 |

+-------------+-------------+--------------+-------------+------------------+

| 8 | 0 | 10000000000 | 9480030367 | 1.68381e+10 |

+-------------+-------------+--------------+-------------+------------------+

| 9 | 0 | 100000000000 | -1 | 1.68892e+10 |

+-------------+-------------+--------------+-------------+------------------+

This is an interesting series of results. As the range of values increases, the length of time to get a hit takes longer. There is even a point where guessing gives no hits! That is great and demands further trials at some point.

Results from second run with seeds 36912 and 707:

+-------------+-------------+--------------+-------------+------------------+

| trial_num | low_fence | high_fence | first_hit | execution_time |

+=============+=============+==============+=============+==================+

| 0 | 0 | 100 | 343 | 518.625 |

+-------------+-------------+--------------+-------------+------------------+

| 1 | 0 | 1000 | 3713 | 5666.25 |

+-------------+-------------+--------------+-------------+------------------+

| 2 | 0 | 10000 | 8849 | 14097 |

+-------------+-------------+--------------+-------------+------------------+

| 3 | 0 | 100000 | 197123 | 304538 |

+-------------+-------------+--------------+-------------+------------------+

| 4 | 0 | 1000000 | 342849 | 517321 |

+-------------+-------------+--------------+-------------+------------------+

| 5 | 0 | 10000000 | 11395292 | 1.8386e+07 |

+-------------+-------------+--------------+-------------+------------------+

| 6 | 0 | 100000000 | 153426619 | 2.41962e+08 |

+-------------+-------------+--------------+-------------+------------------+

| 7 | 0 | 1000000000 | 1836470922 | 2.82947e+09 |

+-------------+-------------+--------------+-------------+------------------+

| 8 | 0 | 10000000000 | 1174999287 | 2.08082e+09 |

+-------------+-------------+--------------+-------------+------------------+

| 9 | 0 | 100000000000 | -1 | 1.68773e+10 |

+-------------+-------------+--------------+-------------+------------------+

I see an interesting repeat here despite the 2 different seed values. Again, this is a simple experiment. It does show that the same PRNG configured slightly differently can generate a hit.

Experiment 2 – Percentages

I will now see if there can be at least one hit found by just guessing at random numbers. The next question is to find out how often that happens per 10,000,000,000 tries? It also seems to be a function on the range of the value. Taking an educated guess, the larger the range, the longer it takes to get a hit. Let’s see if that is true by running an experiment.

Since the seed pairs did not really change the results too far out, I will use seeds of 100 and 200.

Results:

+-------------+--------------+----------+-------------+--------------+---------------+

| trial_num | high_fence | hits | misses | hit perct. | miss perct. |

+=============+==============+==========+=============+==============+===============+

| 0 | 100 | 99024723 | 9900975277 | 0.990247 | 99.0098 |

+-------------+--------------+----------+-------------+--------------+---------------+

| 1 | 1000 | 9983211 | 9990016789 | 0.0998321 | 99.9002 |

+-------------+--------------+----------+-------------+--------------+---------------+

| 2 | 10000 | 999819 | 9999000181 | 0.00999819 | 99.99 |

+-------------+--------------+----------+-------------+--------------+---------------+

| 3 | 100000 | 99723 | 9999900277 | 0.00099723 | 99.999 |

+-------------+--------------+----------+-------------+--------------+---------------+

| 4 | 1000000 | 10103 | 9999989897 | 0.00010103 | 99.9999 |

+-------------+--------------+----------+-------------+--------------+---------------+

| 5 | 10000000 | 982 | 9999999018 | 9.82e-06 | 100 |

+-------------+--------------+----------+-------------+--------------+---------------+

| 6 | 100000000 | 91 | 9999999909 | 9.1e-07 | 100 |

+-------------+--------------+----------+-------------+--------------+---------------+

| 7 | 1000000000 | 14 | 9999999986 | 1.4e-07 | 100 |

+-------------+--------------+----------+-------------+--------------+---------------+

| 8 | 10000000000 | 2 | 9999999998 | 2e-08 | 100 |

+-------------+--------------+----------+-------------+--------------+---------------+

| 9 | 100000000000 | 0 | 10000000000 | 0 | 100 |

+-------------+--------------+----------+-------------+--------------+---------------+This is better than I expected. Look at the first trial 0. See how the percentage is highest at near 1%. I thought it would be even higher.

As the trials expand and become more complex, the hit percentage goes lower. That is expected as there is more of a challenge to the test. I also see that the highest range gets a true 100%.

I wonder if this were to keep running on my modest hardware (MacBook Air M1 16GB), past the limit of 10,000,000,000 tries, would there ever be a hit?

Experiment 3 – Secrets Module

There is a more advanced way to generate random numbers in Python by using the secrets module16. This is more cryptographically strong but pay attention to the fine print. It depends on the most secure method the operating system provides. This caused me to do some reading on the security in MacOS17. *Note: I do want to learn the actual hardware method here. I will need to look further into these features but note the use of the acronym CPRNG, Cryptographic Pseudorandom Number Generators. There is always a new acronym to learn. This implies that there is a strength to the PRNG approach. Working on a project using Apple’s Swift Programming Language might be a useful research endeavor. Remember, choose the right language for the project.

Moving forward with this experiment, I will also create 2 separate RNG instances but will use the SystemRandom() function as-is. In other words, I will not attempt any special configuration. I will just execute a direct function call. For the seed, I am going to let the entropy of the system decide that as it is much more advanced than having me pick a value. From prior experimentation, there is some noticeable slowness with this package so I will set the limiter to 100,000,000.

Result:

Process Completed. Execution Time: 1449065500.875

No hits after 100000000 tries.That is great that it ran but did not get a hit. Still, is this all there is to determine if there is a pattern to RNGs? I doubt that a cracker is merely just taking guesses. Remember, this is a deterministic system. No matter how chaotic, there will always be a pattern. You just need enough values to determine the right method of attack.

Experiment 4 – Hit Test with Secrets Package

Given there is no hit on that previous experiment using the secrets package, I will go back and retry the original experiment of trying to find the first hit. The limit of 10,000,000,000 tries will still be in place. The difference this time is that the process will stop if the limit is reached before a hit takes place. Again, I will let the internal workings of the RNG determine the seed.

Result:

+-------------+--------------+-------------+------------------+

| trial_num | high_fence | first_hit | execution_time |

+=============+==============+=============+==================+

| 0 | 100 | -1 | 5.97903e+10 |

+-------------+--------------+-------------+------------------+This is very encouraging to see for PRNG. Even with such a tight range, there is no hit taking place. Could the internal seed generation be that good? I ran this experiment several more times to make sure it was not anomaly. I still did not get a first hit happen.

For an additional check, I decided to extend the range to the next level where the high fence is 1000. Here is the result:

+-------------+--------------+-------------+------------------+

| trial_num | high_fence | first_hit | execution_time |

+=============+==============+=============+==================+

| 1 | 1000 | -1 | 4.81957e+10 |

+-------------+--------------+-------------+------------------+It’s great that there is no hit but time to hit the reality button again. In each of my experiments, I am merely taking a guess with another guess. I did not expect to get any hits using this method. The results in previous experiments show it is possible to just guess the right value. I hypothesize that many more hits would be seen with more reliable and clever cracking techniques.

True RNGs?

This should then bring up the idea of whether or not a true RNGs exists. Is there anything truly random that could be introduced into this ordered environment? What about a possible solution from Chaos Theory?

The study of Chaos is wonderful and produces so many interesting areas to explore. I do remember first learning about this concept where the entire world’s weather pattern can be changed merely by a butterfly flapping its wings18. Is that mere flap of the wings a stochastic event or is it not fully understood? Like all the other beautiful aspects of the Universe, if we truly understood (and respected) it, would it be unpredictable still?

Philosophy aside, Chaos is not truly random. There are deterministic components at its very core. That makes Chaos not the right solution of randomness.

What about a different type of machine, like a quantum computer? Can a quantum computer be a true random number generator (TRNG) given we are out of the realm of the expected seed/algorithm approach? Many do say yes19 to that question but there might need to be more work20. I am a mere novice with quantum computing at the moment. That certainly never stopped me from trying something before and it will not stop me now. Let’s dive into a quick experiment.

Experiment 5 – Quantum Computing

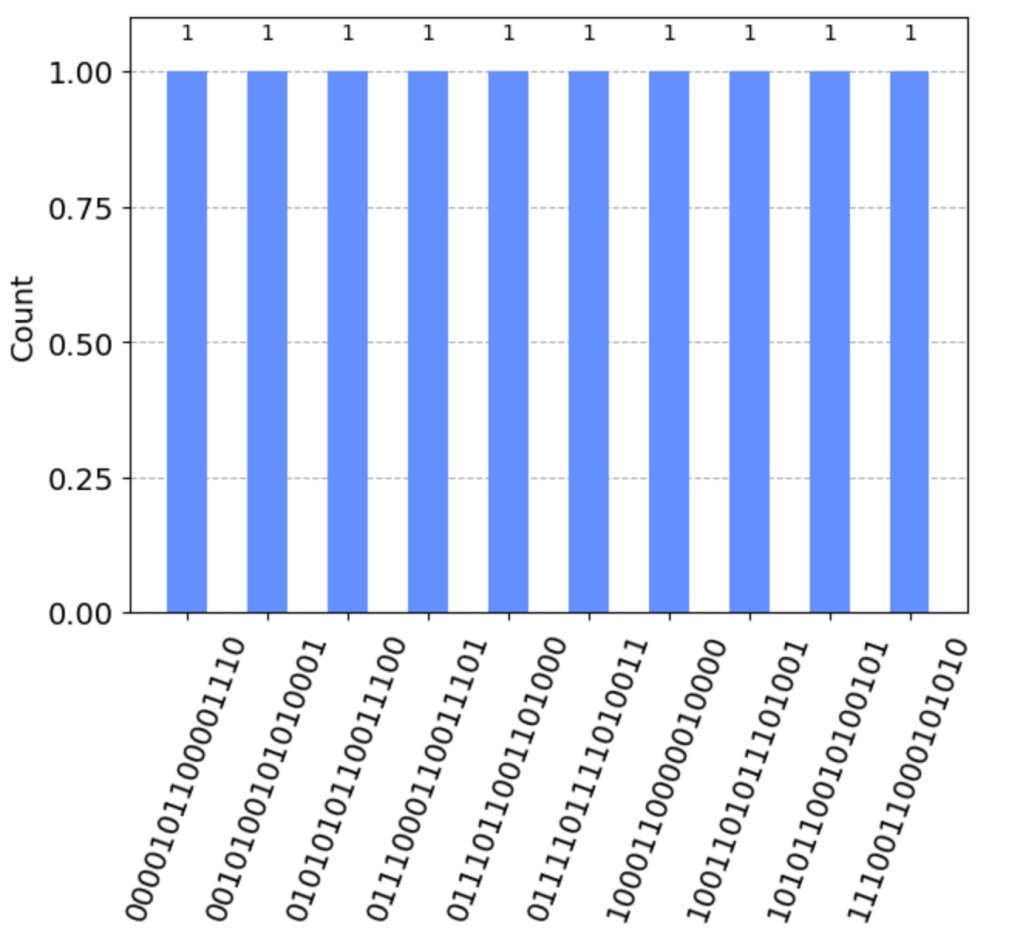

I hesitate to call this much of an experiment. It is more of a demonstration. I will utilize IBM’s Quantum21 provider to show how it is possible to generate a random number. I am certainly not an expert on quantum computing, so I resorted to customizing some code I found using the Qiskit Package22, 23. What this code does is to fashion a series of what is known as Hadamard Gates24. In essence, this approach results in a generated series of values which can be made into a random number

The limits I chose do not create a long enough series of 1’s and 0’s to give true, non-repetitive randomness but take a step back. Look at the results from just 10 generated values:

This chart shows the results of 10 experiments with the circuit along with the counts of each output. You can see it is an even distribution from a probability of each gate being 1 or 0 at 50%. I would think that this distribution would change as duplicates are found. At that point, the circuit might grow to add more complexity.

So, is this a TRNG? If I keep trying with a substantially large quantum circuit, will a pattern emerge?

The theory is that a pattern will not emerge. The nature of the various waves and fields that spin qubits is considered unpredictable therefore making this a TRNG. Is everything fully understood, though?

Could everyone agree that this is truly unpredictable or is it only unpredictable with our current knowledge and skills? Mankind’s knowledge should always be growing. It would be such a waste of our gifts to say that we can know no more. Instead, it should be said that this is what we know as of now, but we will see what can be done tomorrow.

Next Time

This seems like a good spot to pause and think about RNGs. Is anything truly random or is it our naïve understanding of creation that is holding us back? This topic is certainly worth further exploration.

For the next in the series, I will explore how the quality of a RNG can be determined. From early experimentation, there are various methods that include some statistical analysis. I am not sure where it will lead but as they say every journey starts with a single step (or line of code).

Thank you for your time. Have a great day!

Appendix

Code

The code provided here is truly in an AS-IS condition. I change the code often to experiment in many ways. It might not be in an ideal state. Use at your own risk.

Random Sampling Demonstration (Python)

# Title: RNG - Random Sampling Demo

# Author: Andrew Della Vecchia

# Purpose: used for RNG experiments in article for Andrew's Folly (http://www.andrewsfolly.com)

# Conditions: only use in AS-IS condition. This is completely experimental code with no guarantees.

# imports

import pandas as pd

import os

# set wd

os.chdir('')

print(os.getcwd())

# read in the entire set

data_columns_df = list(pd.read_csv('heart_disease_columns.csv'))

heart_disease_df = pd.read_csv('processed.cleveland.data', names=data_columns_df)

# take 2 samples using random method

sample1 = heart_disease_df.sample(10)

sample2 = heart_disease_df.sample(10)

# show the samples as they come out randomly chosen

print(sample1)

print(sample2)Random Network Generation Demonstration (R)

# Title: RNG - Random Network Demonstration

# Author: Andrew Della Vecchia

# Purpose: used for RNG experiments in article for Andrew's Folly (http://www.andrewsfolly.com)

# Conditions: only use in AS-IS condition. This is completely experimental code with no guarantees.

# Load up the libraries

library(igraph)

# Same function call, randomness generates different graph

g1 <- sample_smallworld(dim = 1, size = 100, nei = 2, p = 0.25)

g2 <- sample_smallworld(dim = 1, size = 100, nei = 2, p = 0.25)

# Plot out the results

par(mfrow = c(2,2))

plot(g1, main = 'Graph 1 - Network', vertex.size = 2, vertex.label = NA, layout = layout_as_tree)

plot(degree_distribution(g1), main = 'Graph 1 - Degree Distribution', xlab = 'Degree', ylab = 'Proportion', type = 'b')

plot(g2, main = 'Graph 2 - Network', vertex.size = 2, vertex.label = NA, layout = layout_as_tree)

plot(degree_distribution(g2), main = 'Graph 2 - Degree Distribution', xlab = 'Degree', ylab = 'Proportion', type = 'b')Experiment 1 – Guessing Game (Python)

# Title: RNG Experiment 1 - Guessing Game

# Author: Andrew Della Vecchia

# Purpose: used for RNG experiments in article for Andrew's Folly (http://www.andrewsfolly.com)

# Conditions: only use in AS-IS condition. This is completely experimental code with no guarantees.

import time

import random as rnd

from tabulate import tabulate

# Create 2 RNG instances

rand1 = rnd.Random()

rand2 = rnd.Random()

# set seed

# experiment 1a seeds

#rand1.seed(100)

#rand2.seed(200)

# experiment 1b seeds

rand1.seed(36912)

rand2.seed(707)

#init

trials = 10

results_table_columns = ['trial_num', 'low_fence','high_fence','first_hit', 'execution_time']

results_table = []

# at each trial, increase the high fence by a factor of 10

for trial_num in range(0, trials):

# setup the trial

low_fence = 0

high_fence = 100 * 10**trial_num

first_hit = -1

tries = 0

limiter = 10000000000 # 10,000,000,000

rnd1 = -1

rnd2 = -2

execution_time_start = time.perf_counter()

# try to generate random numbers that are the same

while(rnd1 != rnd2 and tries < limiter):

tries+=1

#generate random numbers

rnd1 = rand1.randint(low_fence, high_fence)

rnd2 = rand2.randint(low_fence, high_fence)

execution_time_stop = time.perf_counter()

execution_time_duration = (execution_time_stop - execution_time_start) * 10**6 # microseconds

first_hit = -1 if tries == limiter else tries

results = [trial_num, low_fence, high_fence, first_hit, execution_time_duration]

results_table.append(results)

# show results

print(tabulate(results_table, headers=results_table_columns, tablefmt='grid'))Experiment 2 – Percentages (Python)

# Title: RNG Experiment 2 - Percentages

# Author: Andrew Della Vecchia

# Purpose: used for RNG experiments in article for Andrew's Folly (http://www.andrewsfolly.com)

# Conditions: only use in AS-IS condition. This is completely experimental code with no guarantees.

# packages

import random as rnd

from tabulate import tabulate

# Create 2 RNG instances

rand1 = rnd.Random()

rand2 = rnd.Random()

# set seed

rand1.seed(100)

rand2.seed(200)

#init

trials = 10

results_table_columns = ['trial_num','tries','low_fence','high_fence','hits','misses', 'hit perct.', 'miss perct.']

results_table = []

# at each trial, increase the high fence by a factor of 10

for trial_num in range(trials):

# setup the trial

hits = 0

misses = 0

low_fence = 0

high_fence = 100 * 10**trial_num

tries = 10000000000 #10,000,000,000

# try to generate random numbers that are the same

for try_num in range(tries):

#generate random numbers

rnd1 = rand1.randint(low_fence, high_fence)

rnd2 = rand2.randint(low_fence, high_fence)

if rnd1 == rnd2:

hits += 1

else:

misses += 1

#Keep a running list of results

results = [trial_num, tries, low_fence, high_fence, hits, misses, (hits/tries) * 100 , (misses/tries) * 100]

results_table.append(results)

# show results

print(tabulate(results_table, headers=results_table_columns, tablefmt='grid'))Experiment 3 – Secrets Module (Python)

# Title: RNG Experiment 3 - Secrets Module

# Author: Andrew Della Vecchia

# Purpose: used for RNG experiments in article for Andrew's Folly (http://www.andrewsfolly.com)

# Conditions: only use in AS-IS condition. This is completely experimental code with no guarantees.

# packages

import secrets

import time

# setup the trial

first_hit = -1

tries = 0

limiter = 100000000

rnd1 = -1

rnd2 = -2

# Create 2 RNG instances

rand1 = secrets.SystemRandom()

rand2 = secrets.SystemRandom()

execution_time_start = time.perf_counter()

# try to generate random numbers that are the same

while(rnd1 != rnd2 and tries < limiter):

tries+=1

#generate random numbers

rnd1 = rand1.randint

rnd2 = rand2.randint

execution_time_stop = time.perf_counter()

execution_time_duration = (execution_time_stop - execution_time_start) * 10**6 # microseconds

print(f'Process Completed. Execution Time: {execution_time_duration}')

if tries == limiter:

print(f'No hits after {tries} tries.')

else:

print(f'Hit after only {tries} tries.')Experiment 4 – Hit Test with Secrets Package

# Title: RNG - Experiment 4 - Hit Test with Secrets Package

# Author: Andrew Della Vecchia

# Purpose: used for RNG experiments in article for Andrew's Folly (http://www.andrewsfolly.com)

# Conditions: only use in AS-IS condition. This is completely experimental code with no guarantees.

# packages

import time

import secrets

from tabulate import tabulate

# Create 2 RNG instances

rand1 = secrets

rand2 = secrets

#init

trials = 10

results_table_columns = ['trial_num', 'high_fence','first_hit', 'execution_time']

results_table = []

trial_num = 0

failure_to_hit = False

# at each trial, increase the high fence by a factor of 10

while trial_num <= trials and failure_to_hit == False:

# setup the trial

high_fence = 100 * 10**trial_num

first_hit = -1

tries = 0

limiter = 10000000000 # 10,000,000,000

rnd1 = -1

rnd2 = -2

execution_time_start = time.perf_counter()

# try to generate random numbers that are the same

while(rnd1 != rnd2 and tries < limiter):

tries += 1

#generate random numbers

rnd1 = rand1.randbelow(exclusive_upper_bound=high_fence)

rnd1 = rand2.randbelow(exclusive_upper_bound=high_fence)

execution_time_stop = time.perf_counter()

execution_time_duration = (execution_time_stop - execution_time_start) * 10**6 # microseconds

first_hit = -1 if tries == limiter else tries

failure_to_hit = True if first_hit == -1 else False

results = [trial_num, high_fence, first_hit, execution_time_duration]

results_table.append(results)

trial_num += 1

# show results

print(tabulate(results_table, headers=results_table_columns, tablefmt='grid'))Experiment 5 – Quantum Computing (Python)

# Title: RNG - Experiment 5 - Quantum Computing

# Author: Andrew Della Vecchia

# Purpose: used for RNG experiments in article for Andrew's Folly (http://www.andrewsfolly.com)

# Conditions: only use in AS-IS condition. This is completely experimental code with no guarantees.

# Reference: https://thequantuminsider.com/2019/11/04/quantum-programming-101-16-qubit-random-number-generator-tutorial/

from qiskit import QuantumRegister, ClassicalRegister, QuantumCircuit

from qiskit_ibm_provider import IBMProvider

from qiskit.visualization import plot_histogram

provider = IBMProvider()

q = QuantumRegister(16, 'q')

c = ClassicalRegister(16, 'c')

circuit = QuantumCircuit(q, c)

circuit.h(q)

circuit.measure(q, c)

backend = provider.get_backend('ibmq_qasm_simulator')

job = execute(circuit, backend, shots=10)

counts = job.result().get_counts()

print(counts)

plot_histogram(counts)References

[1] Killed by Microsoft. Retrieved from: https://killedbymicrosoft.info

[2] Turner, Dawn M. Summary of cryptographic algorithms – according to NIST. Cryptomathic. December 27 2019. Retrieved from: https://www.cryptomathic.com/news-events/blog/summary-of-cryptographic-algorithms-according-to-nist

[3] United States Courts. Learn About Jury Service. Retrieved from: https://www.uscourts.gov/services-forms/jury-service/learn-about-jury-service

[4] Wikipedia. Call of Duty. Retrieved from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Call_of_Duty

[5] Janosi,Andras, Steinbrunn,William, Pfisterer,Matthias, and Detrano,Robert. (1988). Heart Disease. UCI Machine Learning Repository. https://doi.org/10.24432/C52P4X.

[6] Douglas Luke. “A User’s Guide to Network Analysis in R1st ed. 2015”. Springer International Publishing Switzerland. 2015

[7] Mason A. Porter (2012), Scholarpedia, 7(2):1739. Small-world network. Retrieved from: http://www.scholarpedia.org/article/Small-world_network

[8] Angélica. “The Six Degrees of Separation Theory and How It Works.” Exploring Your Mind, Exploring Your Mind, 23 April 2019, Retrieved from: exploringyourmind.com/the-six-degrees-of-separation-theory/

[9] Wikipedia. Small-world experiment. Retrieved from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Small-world_experiment

[10] Csardi G, Nepusz T (2006). “The igraph software package for complex network research.” InterJournal, Complex Systems, 1695. https://igraph.org

[11] Wikipedia. Pentium FDIV Bug. Retrieved from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pentium_FDIV_bug

[12] Wikipedia. List of random number generators. Retrieved from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_random_number_generators

[13] Wikipedia. Trusted Platform Module. Retrieved from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trusted_Platform_Module

[14] random – Generate pseudo-random numbers. Retrieved from: https://docs.python.org/3/library/random.html#module-random

[15] Wikipedia. Mersenne Twister. Retrieved from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mersenne_Twister

[16] secrets – Generate secure random numbers for managing secrets. Retrieved from: https://docs.python.org/3/library/secrets.html

[17] Apple Platform Security – Random Number Generation. Retrieved from: https://support.apple.com/guide/security/random-number-generation-seca0c73a75b/web

[18] Vernon, Jamie L. Understanding the Butterfly Effect. American Scientist, May-June 2017. Retrieved from: https://www.americanscientist.org/article/understanding-the-butterfly-effect

[19] Thankur, Nikin. True randomness with Quantum ( Quantum Random number generator ). July 3, 2023. Retrieved from: https://blogs.sap.com/2023/07/03/true-randomness-with-quantum-quantum-random-number-generator/

[20] A. Ash-Saki, M. Alam and S. Ghosh, “Improving Reliability of Quantum True Random Number Generator using Machine Learning,” 2020 21st International Symposium on Quality Electronic Design (ISQED), Santa Clara, CA, USA, 2020, pp. 273-279, doi: 10.1109/ISQED48828.2020.9137054. Retrieved from: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/9137054

[21] IBM. IBM Quantum. Retrieved from: https://quantum-computing.ibm.com

[22] Coggins, Macauley. Quantum Programming 101: 16 Qubit Random Number Generator Tutorial. November 4, 2019. Retrieved from: https://thequantuminsider.com/2019/11/04/quantum-programming-101-16-qubit-random-number-generator-tutorial/

[23] Qiskit, contributors. Qiskit: An Open-source Framework for Quantum Computing. 2023. Retrieved from: https://qiskit.org

[24] StackExchange, contributors. Discussion: How are the IBM’s and Google’s Hadamard gates fabricated and operated? Initiated: November 12, 2020. Retrieved from: https://quantumcomputing.stackexchange.com/questions/14576/how-are-the-ibms-and-googles-hadamard-gates-fabricated-and-operated

Not referenced but worthwhile to read

Amy Nordrum. A True Random-Number Generator Built From Carbon Nanotubes. August 9, 2017. IEEE Spectrum. Retrieved from: https://spectrum.ieee.org/a-true-random-number-generator-built-from-carbon-nanotubes-promises-better-security-for-flexible-electronics

2 responses to “An Exploration of Random Numbers – Part 1: The Random Number Generator”

[…] *Note: I used random numbers for placement of the different elements in the Christmas Card. Ah! Another use of random numbers! […]

LikeLike

[…] The initial view of a RNG we dove into was pretty simple. RNGs are an algorithm that generate a sequence of numbers that should be unpredictable from previous history. We went into how there really is no “True” RNG (TRNG) with a deterministic system. As a result, we do have pseudo-RNGs (PRNGs). […]

LikeLike