Preface

In this article, I will step through the process of staging data. This entails reviewing, cleansing, and other preparations of the source data to be loaded into tables. This is one of the most underestimated challenges in data engineering.

Staging data properly requires thinking beyond a simple dump from source to target. Trying to do too much upfront might cause harm too. My hope is that the process I layout in this article will be useful to you in your data projects. Always keep in mind the goal is to ingest data to generate useable results.

I am going to define the scope of this article to be on the Catechism of the Catholic Church (CCC)1 Text previously extracted. The CCC is the root source for looking at other sources. This is essential for the project.

Introduction

Up until now, the work for The All Roads Project has been more high level. The final table structures are defined in the previous article. That step does gets more detailed but staging the data will bring us even closer to the atomic parts. We will have to review and deeply understand the source files. There are many files to go through but I think we can find some sort of pattern.

Analysis

First, we will define the rules then we build out the solution. I think this will be some fun. It’s a bit like sleuthing the original publisher’s design thoughts.

Finding a Pattern

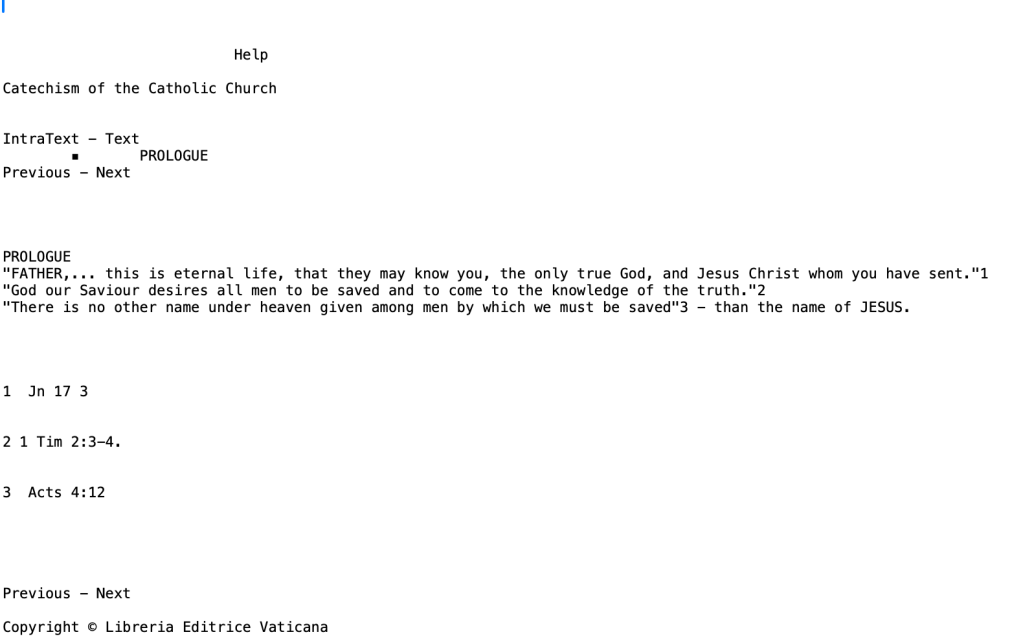

Going past data requirements, I want to see if there is a common layout to the source files. To do this, I always start with a visual inspection. Fortunately, most are similar to the following:

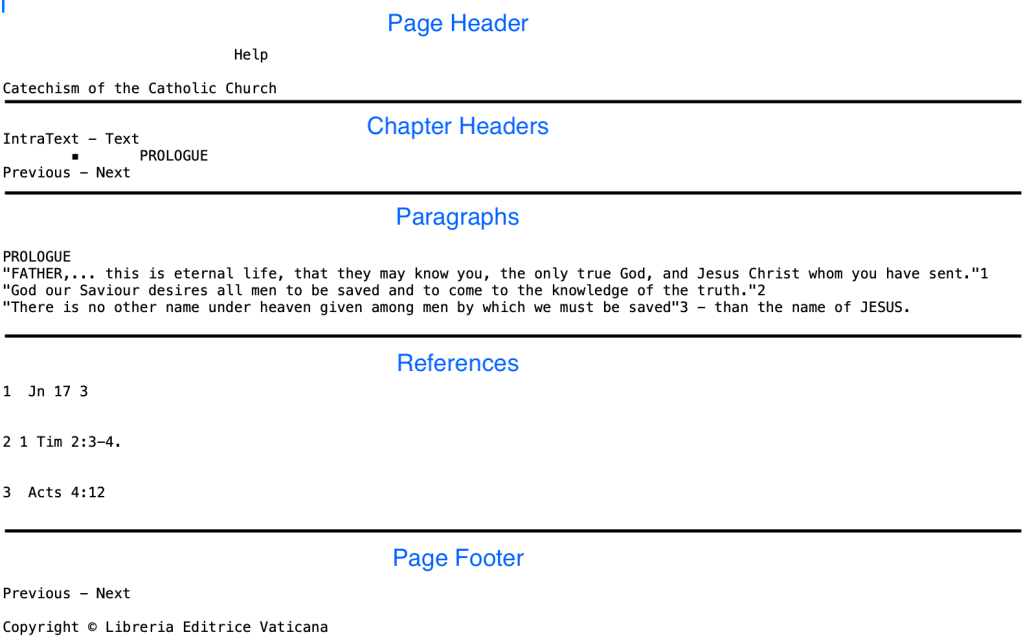

Don’t be overwhelmed in wondering how this is not a CSV, Tab, or other delimited file. Think beyond the commonality found in those formats. If you look a bit more loosely, you will see that there seems to be 5 main parts:

- Page Header

- Chapter Headers

- Paragraphs

- References

- Page Footer

There, that wasn’t difficult to do. How to identify these sections?

Parsing

In each section, see there are common texts. Look at the words “IntraText – Text.” Before it is the page header. Right after it are the chapter headers. That’s 2 sections and we haven’t broke a sweat.

Next, there is “Previous – Next” across the source files. This consistently occurs before and after the paragraphs and references. That’s good but now how to break out the paragraphs from the references?

Look closer and you will see a set of blank lines. Reviewing the files, this turns out to be 3-4 lines in succession. The rules are starting to get a bit more challenging but nothing we can’t handle!

For paragraphs, take note of that numeric identifier. That will need to be captured and separated out. Also, any other numbers indicate a reference citation. Those will need to be separated out too. *Note: not all paragraphs have an identifier. These will be defaulted to -1.

For references, the pattern is common with an identifier along with the cited material. Sometimes, there are multiple citations in one reference. Those concatenated with a semicolon. I warn about parsing out this by semicolon. It’s not a given so analysis might need to be done further down the line.

Finally, the page footer comes at the end. That’s it for the section parsing.

With the components defined, we could just build out the solution now. Asking a question is important here. Is there anything that can be removed as being unnecessary?

Cleansing

For cleansing, it’s possible to get stuck in a never ending set of rules. This is going to be more simple as the CCC is essentially a reference book. We are using this as a book of record and we are not going to change the text. We will not be looking for items such as misspellings

We do have a few items for cleansing. The page header is not needed. Also, the page footer is not needed. We already understand this is the CCC and there is a copyright (which will be followed in any publications). Those two are not needed for analysis.

The blank lines will be removed too. That will be done after their use for parsing is complete. I’d rather save the space even though storage is relatively cheap (except for Apple Products).

Finally, non-printable characters will be removed. This is not easy and might require manual editing as needed. Yes, it is laborious to do, but is essential to get done.

Traceability

If we accept that there are no technical hurdles for parsing and cleansing, it should be a simple matter of putting it into a table. I’ll hold up a caution flag and say the word developers understand all too well: “debugging.” What if something goes wrong and we cannot trace it back? We will need some method to go backwards to the original source.

For each row, I will require:

- The page name this row comes from.

- The line number this row is at in the page.

- The sequential line number in the section (1, 2, 3 for header, paragraphs, and references).

These should give us the necessary traceability to get back to the right area in the source. If there is a problem in processing, we can follow multiple debugging techniques.

Cleansed File Structure

The resulting files will have the following field layout:

Headers (file name will be: “CCC.” followed by extract number, “.h.txt”)

- File_Name

- Page_Line_Number

- Header_Line_Number

- Header_Text

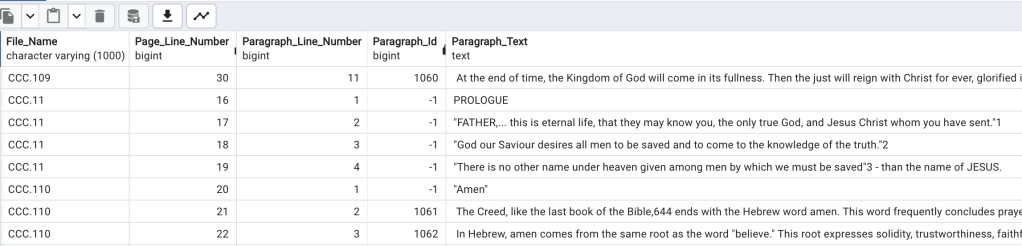

Paragraphs (file name will be: “CCC.” followed by extract number, “.p.txt”)

- File_Name

- Page_Line_Number

- Paragraph_Line_Number

- Paragraph_Id

- Paragraph_Text

- References

References (file name will be: “CCC.” followed by extract number, “.r.txt”)

- File_Name

- Page_Line_Number

- Reference_Line_Number

- Reference_Id

- Reference_Text

I will rely on the rules and file layouts as the design documentation needed to build the parsing and cleansing process. A formal source to target mapping (STTM) could be a bit confusing. That effort will be done with the database ingestion process. We now have enough material and direction to start building.

Building

Given that there are customized and specific rules, I decided not to go with a pre-built tool. They can be very useful in enterprise environments. In this circumstance, a common programming language with text parsing, such as Python, will be more flexible. After much thought, I went even simpler and decided upon our friend awk.

It is built into many OS’es, including MacOS, and performs extremely well. If you can understand regular expression syntax, then this is the tool to use for text parsing and organization. All that is needed is a text editor and a command prompt open. Pretty IDEs are nice too but not always a given.

The resulting awk script is in the appendix. This did not take long at all. The analysis is the hardest part. Coding it reminded me of how the original efforts in Bell Labs2 still have use today.

As a final step, I gathered together the created files into 3 master files:

- CCC.all.h.txt for all of the extracted headers.

- CCC.all.p.txt for all of the extracted paragraphs.

- CCC.all.r.txt for all of the extracted references

This makes the import step easier with 1 file for each table. If not, a separate script will need to be created to process the multitude of files.

Validation

Before staging into the database, there needs to be some validation effort run. This is going to be tricky. The reason is that there has been some cleansing of blanks and redundant text. There are also additions of delimiters (pipe is chosen), line numbers, and identifiers. This all means that counts will not be an exact match. Going through and visually spot checking many files, it certainly does look like the process worked. However, let’s see if we can guesstimate some sort of response.

We might be able to estimate a value taking the previous determined number of lines as a base. Here are some of the metrics previously captured:

- # of files: 374

- # of lines: 26153

- # of words: 275089

Using the number of lines as a primary metric, let’s determine what is removed during the cleansing process.

Blank lines:

- 6 before header

- 4 after header/before paragraph

- 4 after paragraph/before references

- 2 in-between references (the number of references per file is variable). Running some quick statistics on the files, the average turns out to be 12.5 references per page. This seems very high. I will guesstimate at 10 references per page as a good measure. This gives for 20 blank lines.

- 5 after references

Total: ~39 lines per file

Removed text:

- 2 lines containing “Previous-Next”

- 1 line containing “IntraText – Text”

- 1 line containing “Help”

- 1 line for CCC Title

- 1 line for copyright notice

Total: ~6 lines per file

With 374 files and ~45 lines being removed per file, that is 16830 lines. That brings the line count down to ~9323 lines.

Running a line count on the different files, we have:

- CCC.all.h.txt: 1705 lines

- CCC.all.p.txt: 4507 lines

- CCC.all.r.txt: 3684 lines

Total: 9896 # of lines

That’s a difference of 573 lines. This is probably due to the variability in the number of references mentioned earlier. I would say that is good for a guesstimate. Still, more manual spot checking is done to look for duplicates, truncated lines, etc. With that complete, I feel confident that the process is working as expected.

*Note: the URLs file from the data collection stage is 374 lines.

Defining the Staging Area

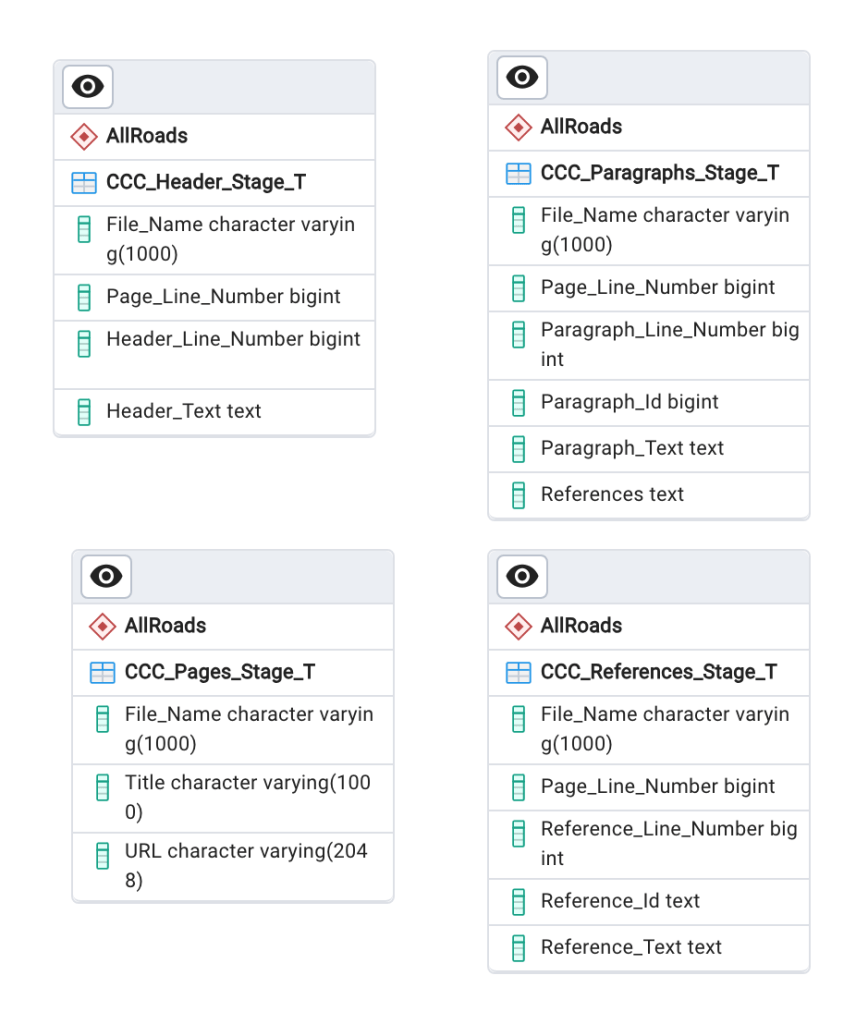

This might seem like cheating, but I decided to design the staging tables to match the processed source material. There are 4 tables:

- CCC_Pages_Stage_T (*Note: this is just the url source from the previous article on pulling the data)

- CCC_Headers_Stage_T

- CCC_Paragraphs_Stage_T

- CCC_References_Stage_T

Using the ERD Tool in pgAdmin, the following definition results:

There are no foreign keys between these tables. I also decided against setting a primary key. This is purely for simplicity sake, but one can truly be defined for each. The DDL is in the appendix and should be steady for the rest of the project.

Staging the Data

A source to target mapping is needed for clarity. It’s important for blueprinting purposes despite the design being 1:1 between file and source. Here are the resulting maps:

| Source File | Source Field Position | Transformation | Target Database | Target Table | Target Field |

| extracted_urls.vatican.ccc.all.txt | 1 | None | AllRoads | CCC_Pages_Stage_T | File_Name |

| extracted_urls.vatican.ccc.all.txt | 2 | None | AllRoads | CCC_Pages_Stage_T | Title |

| extracted_urls.vatican.ccc.all.txt | 3 | None | AllRoads | CCC_Pages_Stage_T | URL |

| Source File | Source Field Position | Transformation | Target Database | Target Table | Target Field |

| CCC.all.h.txt | 1 | None | AllRoads | CCC_Header_Stage_T | File_Name |

| CCC.all.h.txt | 2 | None | AllRoads | CCC_Header_Stage_T | Page_Line_Number |

| CCC.all.h.txt | 3 | None | AllRoads | CCC_Header_Stage_T | Header_Line_Number |

| CCC.all.h.txt | 4 | None | AllRoads | CCC_Header_Stage_T | Header_Text |

| Source File | Source Field Position | Transformation | Target Database | Target Table | Target Field |

| CCC.all.p.txt | 1 | None | AllRoads | CCC_Paragraphs_Stage_T | File_Name |

| CCC.all.p.txt | 2 | None | AllRoads | CCC_Paragraphs_Stage_T | Page_Line_Number |

| CCC.all.p.txt | 3 | None | AllRoads | CCC_Paragraphs_Stage_T | Paragraph_Line_Number |

| CCC.all.p.txt | 4 | None | AllRoads | CCC_Paragraphs_Stage_T | Paragraph_Id |

| CCC.all.p.txt | 5 | None | AllRoads | CCC_Paragraphs_Stage_T | Paragraph_Text |

| CCC.all.p.txt | 6 | None | AllRoads | CCC_Paragraphs_Stage_T | References |

| Source File | Source Field Position | Transformation | Target Database | Target Table | Target Field |

| CCC.all.r.txt | 1 | None | AllRoads | CCC_References_Stage_T | File_Name |

| CCC.all.r.txt | 2 | None | AllRoads | CCC_References_Stage_T | Page_Line_Number |

| CCC.all.r.txt | 3 | None | AllRoads | CCC_References_Stage_T | Reference_Line_Number |

| CCC.all.r.txt | 4 | None | AllRoads | CCC_References_Stage_T | Reference_Id |

| CCC.all.r.txt | 5 | None | AllRoads | CCC_References_Stage_T | Reference_Text |

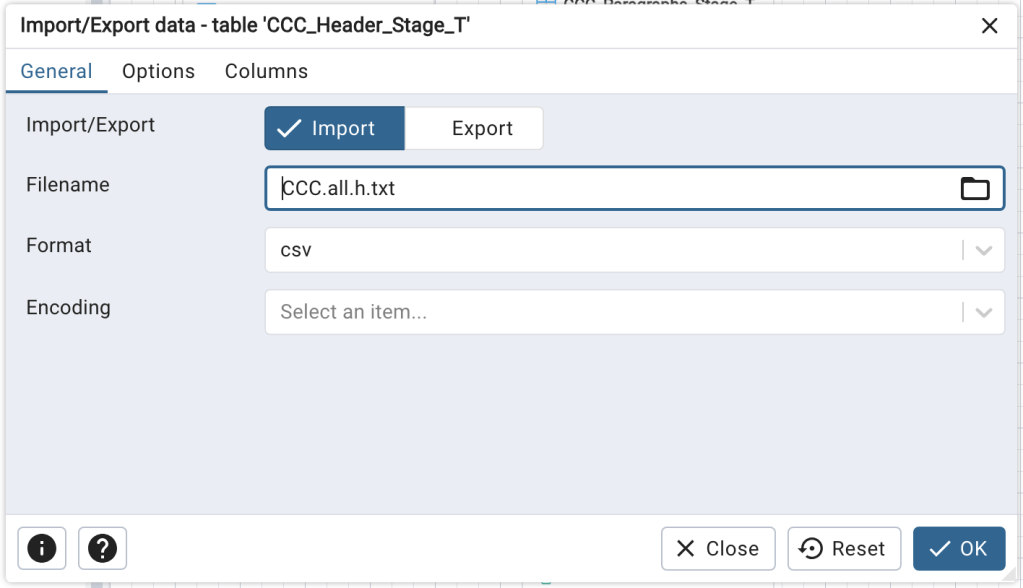

As you can see, a STTM can be flexible and easy to do. Next up, let’s stage these files! This is where having a great database such as PostgreSQL3 is essential. Loading these data is a matter of using pgAdmin’s import utility.

Let’s take a look at the results to make sure.

Validation Again

This validation step should be very accurate. It should be 1:1 in terms of record counts. The results are:

- CCC_Pages_Stage_T: 374 records

- CCC_Headers_Stage_T: 3684 records

- CCC_Paragraphs_Stage_T: 4507

- CCC_References_Stage_T: 1705 records

That lines up as expected. We could do a similar exercise with a word count. I am going to trust my visual spot check of the resulting tables. All seems right in its place. This completes the staging efforts for the CCC.

Next Steps

As previously suggested, staging data is an important step in the ingestion process. It is not always a direct copy but it always requires proper analysis. The end results show that there are now usable data. I can now move forward with loading records into the final structure. I will also take care of the abbreviation list as straight load. After that is complete, I will then be able to add-on other texts and get to some research!

Thank you

Appendix

DDL Script

BEGIN;

CREATE TABLE IF NOT EXISTS "AllRoads"."CCC_Header_Stage_T"

(

"File_Name" character varying(1000) NOT NULL,

"Page_Line_Number" bigint NOT NULL,

"Header_Line_Number" bigint NOT NULL,

"Header_Text" text NOT NULL

);

CREATE TABLE IF NOT EXISTS "AllRoads"."CCC_Paragraphs_Stage_T"

(

"File_Name" character varying(1000) NOT NULL,

"Page_Line_Number" bigint NOT NULL,

"Paragraph_Line_Number" bigint NOT NULL,

"Paragraph_Id" bigint NOT NULL,

"Paragraph_Text" text NOT NULL,

"References" text

);

CREATE TABLE IF NOT EXISTS "AllRoads"."CCC_References_Stage_T"

(

"File_Name" character varying(1000) NOT NULL,

"Page_Line_Number" bigint NOT NULL,

"Reference_Line_Number" bigint NOT NULL,

"Reference_Id" text NOT NULL,

"Reference_Text" text NOT NULL

);

CREATE TABLE IF NOT EXISTS "AllRoads"."CCC_Pages_Stage_T"

(

"File_Name" character varying(1000) NOT NULL,

"Title" character varying(1000) NOT NULL,

"URL" character varying(2048) NOT NULL

);

END;awk Script (named: ccc_extract_info.awk)

# Date: 02-APR-2024

# Author: Andy Della Vecchia

# Purpose: Parse out paragraph references from source files

BEGIN {

# these are used to track where the read is in the file

section_number = 0

blank_line_count = 0

subsection_number = 0

page_line_number = 0

h_line_number = 0

p_line_number = 0

r_line_number = 0

# get the file name being processed

split(ARGV[1], file_pieces, ".")

fn = "CCC." file_pieces[length(file_pieces)-1]

# build out the individual file names (h=header; p=paragraph; r=references)

out_path = "./out/"

header_file = out_path fn ".h.txt"

paragraph_file = out_path fn ".p.txt"

reference_file = out_path fn ".r.txt"

}

{

# track line number for debugging purposes

page_line_number++

# when the "Previous - Next" is found

if ($0 ~ /Previous - Next/ || $0 ~ /IntraText - Text/) {

# Track the section

section_number++

} else {

# section 1 is the header section

if (section_number == 1 && NF != 0) {

# 1 - File Name

# 2 - Page Line # (sequential for each page)

# 3 - Header line # (sequential for each header line #)

# 4 - Header Text

h_line_number++

gsub(/[^a-zA-Z0-9 ]/, "")

print fn "|" page_line_number "|" h_line_number "|" $0 > header_file

# section 2 is the main section with the paragraph and references

} else if (section_number == 2) {

# if not a blank line or a very small text

if (NF != 0 && length($0) > 2) {

# subsection 1 is the paragraphs

if (subsection_number == 1) {

# split the line

# 1 - File Name

# 2 - Page Line # (sequential for each page)

# 3 - Paragraph line # (sequential for each paragraph #)

# 4 - Paragraph Id (if doesn't exist, -1)

# 5 - Text (including reference #s)

# 6 - References - comma delimited

p_line_number++

ref_nums = ""

# if the first field has an id, separate it out, otherwise, use -1

if ($1 ~ /[0-9]+/ && !($1 ~/[A-Za-z+]/)) {

gsub(/[.]/, "", $1)

$1 = fn "|" page_line_number "|" p_line_number "|" $1 "|"

p_id_exists = 0

} else {

$1 = fn "|" page_line_number "|" p_line_number "|" "-1" "|" $1

p_id_exists = 1

}

# find any numeric values and pull out as reference Ids

for (i=2 + p_id_exists; i<=NF; i++) {

if ($i ~ /[0-9]+/) {

bkp_fld = $i

gsub(/[^0-9+]/, "", $i)

if (ref_nums != "") {

ref_nums = ref_nums "," $i

} else {

ref_nums = $i

}

# make sure original field is restored

$i = bkp_fld

}

}

# add on the reference numbers and print out to file

$0 = $0 "|" ref_nums

print $0 > paragraph_file

# subsection 2 is where the references are stored

} else if (subsection_number == 2) {

# 1 - File Name

# 2 - Page line number

# 3 - reference line number

# 4 - Reference Id from text

# 5 - References

r_line_number++

$1 = fn "|" page_line_number "|" r_line_number "|" $1 "|"

print $0 > reference_file

}

# remember that there are no blank lines

blank_line_count = 0

# blank line condition

} else {

blank_line_count++

if (blank_line_count >= 3) {

subsection_number++

blank_line_count = 0

}

}

}

}

}Shell Script to Run awk Process (named: run_ccc_extract.sh)

for in_file in ../../data/CCC/*.txt; do

echo $in_file

awk -f ccc_extract_info.awk $in_file

doneReferences

[1] Vatican. Catechism of the Catholic Church. Retrieved from: https://www.vatican.va/archive/ENG0015/_INDEX.HTM

[2] Free Software Foundation. History of awk and gawk. Retrieved from: https://www.gnu.org/software/gawk/manual/html_node/History.html

[3] The PostgreSQL Global Development Group. PostgreSQL: The World’s Most Advanced Open Source Relational Database. Retrieved from: https://www.postgresql.org/

You must be logged in to post a comment.